Get out Whale You Still Can!

How Sperm whales in the 19th century shared ship attack information

It’s not news that cetaceans are smart, social creatures – we continue to be amazed by new studies as they materialise and the latest one on large scale communication between sperm whales in the 19th century is nothing short of fascinating.

A remarkable new study on how whales behaved when attacked by humans in the 19th century has implications for the way they react to changes inflicted by humans in the 21st century. The paper, published by the Royal Society, addressed the age-old question ‘if whales are so smart, why did they hang around to be killed?’ Well, it turns out that they didn’t!

Whalers in action. Historical view from the 19th century. Wood engraving after a painting (The Flurry, c. 1848) by William Charles Duke (Irish-Australian painter, 1814 – 1853) in Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts (Hobart, Tasmania, Australia), published in 1869

The joys of technology allowed for 19th century logbooks to be digitised, making data analysis a cinch for the scientists. These newly digitised logbooks detailing the hunting of sperm whales in the north Pacific showed that within just a few years the strike rate of the whalers’ harpoons fell by 58%. So how could this have happened? The simple answer is that these super smart cetaceans shared what was happening to them between their populations and critically changed their behaviour as a result. This meant that as the news spread, more and more whales avoided the harpooners’ wrath and a dismal fate leaving them to hunt squid another day.

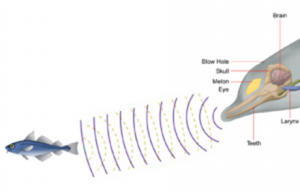

Sperm whales are highly socialised animals, able to communicate over great distances. They associate in clans defined by the dialect (language) of their sonar clicks.

Toothed whales, including dolphins and sperm whales, use echolocation to detect prey (sonar). They emit pulses of sound (clicks) and then listen for the echoes that return after bouncing off of an object ahead of them, such as a fish. (Figure source: Achat1999, Wikimedia Commons)

Toothed whales, including dolphins and sperm whales, use echolocation to detect prey (sonar). They emit pulses of sound (clicks) and then listen for the echoes that return after bouncing off of an object ahead of them, such as a fish. (Figure source: Achat1999, Wikimedia Commons)

Their culture is matrilinear – this means that information is passed on through the female line – information about the new dangers may have been passed on in the same way matriarchs share knowledge about feeding grounds. Sperm whales have the largest brain on the planet so it is hardly surprising they understood what was happening to them!

The hunters’ themselves realised the whales’ efforts to escape. They saw that the animals appeared to communicate the threat within their attacked groups. Abandoning their usual defensive formations, the whales swam upwind to escape hunter’s ships, themselves wind powered.

As whale populations begin to recover from 19th century whaling exploitation, they face new threats created by our technology – they’re having to learn not to get hit by ships, the perils of longline fishing and the changing source of their food due to climate change. Perhaps the biggest and sadly most unavoidable threat is noise pollution. These wily whales are doing their best to adapt but they need our help; the fall in the number of ships on the oceans during the pandemic has seen all kinds of promising signs that with less disturbance our cetacean friends will come roaring back, but, in the long run, it’s people like you talking about our environment and pushing for change that will make the real difference.

A group of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) all a-slumber! Sperm whales sleep vertically in the water column looking serene and spooky all at the same time! Photo: National Geographic.

By Mary-Anne Jones